Alejandro Rebolledo Divided the Country

1

First Limitation:

I’m writing this near Barcelona, but the one in Anzoátegui state, Venezuela. An old private joke from the year Alejandro Rebolledo wrote Poemas del distroy, Juan Barreto won the elections for the mayorship of Caracas, and Andrés González Camino and I met up in Barcelona, Spain (2004). Diego Sequera, who stayed in Caracas, wrote it: “I’m in Barcelona but the one in Anzoátegui, motherfucker.”

I won’t call you a motherfucker (dear reader), but I am close to the Barcelona in Anzoátegui, and Andrés is in that other Barcelona right now, from where he gave me the news of Alejandro Rebolledo’s death.

2

Second Limitation:

I’m writing this text from memory. Just like the public classes Adriano (González León) gave, and the private rounds of drinking with Adriano, to which an enormous percentage of writers from three generations have had access. From my generation, through his son Andrés. From Rebolledo’s generation, thorough his daughter Giorgiana, I suppose, though not that many. And from Adriano’s, through Adriano himself.

3

Third Limitation:

I didn’t read Pim Pam Pum either. I tried to fourteen years ago and it didn’t hook me. From what people say (that it’s the novel of the nineties) I suppose it’s because the type of rebel I was never quite adapted to the consensual rebellion that Urbe magazine sold.

Later on I got half way through it, when Andrés went to visit me in Buenos Aires and brought it with him. I didn’t finish reading it because I felt it became simply annoying. But I do recognize that at first it seemed alright to me.

4

Fourth Limitation:

Saying Alejandro Rebolledo (1970-2016) divided the country is only true if we’re talking about that minuscule part of the country that’s the radius of influence of Venezuelan literature and bougie-punk nerds. So it’s precisely that minuscule part of the country that I’m talking about, because for that part of the country Rebolledo has been for at least a few days the last name that gives a form to a visceral, ferocious and extensive confrontation, which although it’s mobilized by the affective (and maybe precisely for that reason), seems to determine sides in a logic that doesn’t belong to the omnipresent national polarization.

(For the reader who doesn’t belong to that part of the country: the most successful writer of my generation, Rodrigo Blanco Calderón, wrote a lapidary and vitriolic article against the literary hagiography surrounding the recently-deceased author of the novel Pim Pam Pum (1998/2010) created on social media by his readers and mourners. And the reactions, responses and opinions continue to multiply).

5

Fifth and Final Limitation, and Our Main Point:

It could be that the passions will subside a long time from now or soon. But elements already exist that make us affirm that the Blanco Calderón-Rebolledo affair is the first literary schism of the 21st century in Venezuela, as José Ignacio Calderón suggested to me yesterday.

The first schism in the 21st century Venezuelan literary field, as we all know, wasn’t a literary schism, and it still persists. It’s the schism called Bolivarian Revolution or Chavismo, which didn’t create new readings in the field, or disputes regarding ways of reading and defining what the literary might be, but instead subsumed them in the ideological horizon.

6

The literary aspect in that schism has been functional for one of the groups in the dispute. Because as we proposed a while ago here: the best Chavista writing isn’t literature, and if there are Chávistas who write good literature, the good things about that literature isn’t that they’re Chavistas, in the same way that the good things about their Chavismo isn’t the literary.

Did Gustavo Pereira, Luis Britto García, Earle Herrera, José Roberto Duque or Juan Calzadilla become worse writers because they’re Chavistas? No. Chavismo (auto) expelled them from the spaces of literary valuation.

7

I detect small but significant symptoms in the Urbe-Prodavinci affair, a disposition of logics that subvert and transcend that non-literary schism that’s symmetrical to the national polarization.

For one, I identified almost completely with the article by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón (with whom I don’t have a single political idea in common) when I read it for the first time. First because I reject that postmodern nineties Fukuyama cool cynicism that Rebolledo and Pim Pam Pum represent. And second because of its invitation to look beyond the Los Palos Grandes neighborhood of Caracas and to read two of those writers who by means of their Chavismo were (auto) expelled from the literary scene.

8

Once I understood the affective, social and cultural dimensions of the Pim Pam Pum phenomenon, and of Rebolledo’s non-visible work as a DJ and promoter (just like there’s a non-visible work in Adriano’s drinking sessions, keeping in mind the obvious differences), I reread Blanco Calderón’s article and I understand the concerns it raised among many people. Regardless, the experiment was already made: when I shared the article, I found immediate empathy and resonance among people in my own ideological spectrum. Mercedes Chacín, editor of Épale CCS, shared the article by Blanco Calderón who a few weeks ago told the European press that Chavismo is an illiterate dictatorship; Giordana García Sojo asked me if I have a copy of Blanco Calderón’s new novel The Night, so she could borrow it. In the following hours, I noticed figures from the up until now monochord literary world in Venezuela pushing beyond their limits in the tone of a dispute between the Chavista-dominated Esquina Caliente of downtown Caracas and the opposition neighborhood of El Cafetal.

9

Someone (me yesterday, for example) could say this isn’t a literary dispute but rather a show-business, generational and affective one. But literature is also made of all those aspects, just like it’s made of politics. What’s happening is that the way people understand politics in this dispute is different from the great narratives of war and dictatorship.

The article that unleashes it isn’t the most legible starting point, because it’s an article that rejects reading. But precisely for that reason it reveals the discussion of the literary field in all its crudity: it’s a discussion about what should and shouldn’t be read.

That’s why I don’t rule out that Rebolledo or Blanco Calderón might be good points to begin looking at the only place where (as I already said) the literature of Chavismo can be found: in the ways of reading (or no longer reading in the future).

After all, if the poet Chávez cited in his final speech was Borges, there’s no reason to expect the literature of Chavismo be written by those we call “of the left.”

{ Eduardo Febres, Contrapunto, 26 August 2016 }

Showing posts with label Contrapunto. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Contrapunto. Show all posts

8.28.2016

10.08.2015

¿Y dónde está la literatura del chavismo? (algunas sentencias lapidarias) / Eduardo Febres

And Where is the Literature of Chavismo? (A Few Lapidary Precepts)

1

Chavista literature is a contradiction. An aporia. In any form of Chavista writing the weight of the anchoring Chávez/Chavismo turns any horizon different from the political one into nothing. It subordinates and subsumes it. And more so if it’s a horizon as fragile as the literary one. My neighbor Aquiles Zambrano wrote about this in an episode of lucidity: “If it’s Chavista then it isn’t literature: it’s Chavismo, in other words, a political discourse.”

2

Chavista writing, if it’s authentic, is political, and its horizon is the possible, which isn’t always verifiable, but does point towards the truth. That’s why the best Chavista writing isn’t literature, and if there are Chavistas who write good literature, the good aspects of that literature are not that they’re Chavista, in the same way that the good aspects about their Chavismo aren’t the literary ones.

“Today’s events are what matter. But more than writing them, they must be produced,” could be a key phrase for the Chavista writer.

3

That was written by Rodolfo Walsh in 1969, in a private diary (published in Argentina in the 1990s), where the same tension moves through all the pages more or less from 1968 onwards. A tension the editor of those private papers (Daniel Link) condenses into “there’s no separation between life and literature.” But it gets better on the scene in this anecdote from the diary: “The time I should have spent on the novel I spent, mostly, in founding and directing the weekly for the CGT (General Central for Workers).”

You can rest assured that during these past fifteen years the time for writing novels of the best Chavista writers has likewise not been dedicated to the novel. And if there’s something similar to what we can call “Chavista literature,” one of the places to look for it is in the possible diary, or the email inbox, of one of those writers: in a writing that transforms into text the conflict described by Juan Calzadilla: “Not being able to choose action is always the fate and tragedy of all poetry.”

4

That conflict can end up producing a very potent writing, between the irreversible addiction to literature and the deep conviction that: “All males should ignore and curse literature. Reading it is a dissipation worthy, at most, of the harem’s deceitful odalisques and perverse eunuchs. ”

A lapidary precept by our Caribbean poète maudit, José Antonio Ramos Sucre, who also passed through and experimented that tension, although he never got close to political life except by accident, and in fact fled from the world and from life.

Nevertheless, his imaginary, isolated, bookish and self-destructive manner of living heroically produced a writing much more revolutionary, for example, than that of his contemporary Andrés Eloy Blanco, who really was a poet of the people, and definitely wanted to place his literature at the service of revolution.

Revolutionary literature has rarely been made by those who wanted to serve political revolution with literature, and it has always been made by those who have aimed to go beyond the limits of what is known and read as literature in their time.

The best place to look for the literature of Chavismo is in the future, or in forms of reading (or not reading) in the future.

5

One place where you definitely won’t find the literature of Chavismo is in established literature. Though there are plenty of writers who’ve tried to simplify (and capitalize) the storm of Chavismo from the comfort of that literature, all of them have crashed straight into what Che already warned against in 1965, in Socialism and Man in Cuba: “Authentic artistic research is annulled and the problem of general culture is reduced to an appropriation of the socialist present and the dead (but not too dangerous) past. This is how socialist realism is born.”

{ Eduardo Febres, Contrapunto, 7 October 2015 }

1

Chavista literature is a contradiction. An aporia. In any form of Chavista writing the weight of the anchoring Chávez/Chavismo turns any horizon different from the political one into nothing. It subordinates and subsumes it. And more so if it’s a horizon as fragile as the literary one. My neighbor Aquiles Zambrano wrote about this in an episode of lucidity: “If it’s Chavista then it isn’t literature: it’s Chavismo, in other words, a political discourse.”

2

Chavista writing, if it’s authentic, is political, and its horizon is the possible, which isn’t always verifiable, but does point towards the truth. That’s why the best Chavista writing isn’t literature, and if there are Chavistas who write good literature, the good aspects of that literature are not that they’re Chavista, in the same way that the good aspects about their Chavismo aren’t the literary ones.

“Today’s events are what matter. But more than writing them, they must be produced,” could be a key phrase for the Chavista writer.

3

That was written by Rodolfo Walsh in 1969, in a private diary (published in Argentina in the 1990s), where the same tension moves through all the pages more or less from 1968 onwards. A tension the editor of those private papers (Daniel Link) condenses into “there’s no separation between life and literature.” But it gets better on the scene in this anecdote from the diary: “The time I should have spent on the novel I spent, mostly, in founding and directing the weekly for the CGT (General Central for Workers).”

You can rest assured that during these past fifteen years the time for writing novels of the best Chavista writers has likewise not been dedicated to the novel. And if there’s something similar to what we can call “Chavista literature,” one of the places to look for it is in the possible diary, or the email inbox, of one of those writers: in a writing that transforms into text the conflict described by Juan Calzadilla: “Not being able to choose action is always the fate and tragedy of all poetry.”

4

That conflict can end up producing a very potent writing, between the irreversible addiction to literature and the deep conviction that: “All males should ignore and curse literature. Reading it is a dissipation worthy, at most, of the harem’s deceitful odalisques and perverse eunuchs. ”

A lapidary precept by our Caribbean poète maudit, José Antonio Ramos Sucre, who also passed through and experimented that tension, although he never got close to political life except by accident, and in fact fled from the world and from life.

Nevertheless, his imaginary, isolated, bookish and self-destructive manner of living heroically produced a writing much more revolutionary, for example, than that of his contemporary Andrés Eloy Blanco, who really was a poet of the people, and definitely wanted to place his literature at the service of revolution.

Revolutionary literature has rarely been made by those who wanted to serve political revolution with literature, and it has always been made by those who have aimed to go beyond the limits of what is known and read as literature in their time.

The best place to look for the literature of Chavismo is in the future, or in forms of reading (or not reading) in the future.

5

One place where you definitely won’t find the literature of Chavismo is in established literature. Though there are plenty of writers who’ve tried to simplify (and capitalize) the storm of Chavismo from the comfort of that literature, all of them have crashed straight into what Che already warned against in 1965, in Socialism and Man in Cuba: “Authentic artistic research is annulled and the problem of general culture is reduced to an appropriation of the socialist present and the dead (but not too dangerous) past. This is how socialist realism is born.”

{ Eduardo Febres, Contrapunto, 7 October 2015 }

2.07.2015

Libros Lugar Común mide el pulso a lo que se está escribiendo en Venezuela / Hensli Rahn Solórzano

Libros Lugar Común Measures the Pulse of What’s Being Written in Venezuela

[Rodrigo Blanco and Luis Yslas, by Carlos Ancheta]

Within a few years, the publishing house Lugar Común has become a point of reference on Venezuelan bookshelves. Contrapunto spoke with the two writers who run the publishing house, Rodrigo Blanco and Luis Yslas.

Hensli Rahn Solórzano.- Blame it on the Venezuelan novelist Francisco “Pancho” Massiani. One afternoon, two graduates of the School of Letters at the Central University of Venezuela, the editor Luis Yslas and the young UCV professor Rodrigo Blanco, coincided at his house.

The common goals shared by this pair moved them to take on the project ReLectura, a type of lab or “training camp” that would help them in the eventual foundation of the publishing house that concerns us today: Libros Lugar Común [Commonplace Books].

“After an exchange of possible names, we were tired and eventually everything we suggested was commonplace,” recalls the writer Luis Yslas about their name. “I thought that could be the name, understanding it as a space for gathering in a common space, of similar interests... playing with the double meaning of the phrase.”

In 2013, Yslas and Blanco, along with other associates, opened the Lugar Común Bookstore in the east side of Caracas. The establishment very soon became a stage for musical groups, a classroom for literary workshops and a space for presenting new books. This is how the “Lugarcomunistas” made a name for themselves in Caracas.

However, “now the publishing house and bookstore proceed independently,” clarifies Rodrigo Blanco, the author of three collections of short stories and an unpublished novel.

Since its foundation until today, Libros Lugar Común has been a witness to the passing of time and the changes being generated in Venezuela. In their own words, they have passed through the contraction of the editorial market in 2012, the paper shortage crisis of 2013-2014, and the devaluations of the bolivar that now affect the price of books. What follows is the rest of the story as told to Contrapunto by the founders of the publishing house.

How did you both meet and how did you decide to start the project ReLectura in 2007?

LY: We coincided one afternoon at Pancho Massiani’s house. From then on, we shared conversations, affinities as readers, beers at the local Chinese restaurants (our first and improvised operation headquarters). Two years later, the novelist Federico Vegas invited us to participate in a project he had in mind. He wanted to promote encounters between readers and writers, by means of gatherings, readings, book exchanges, and also through a webpage that ended up becoming a type of literary magazine. That’s how ReLectura emerged.

Is ReLectura —the webpage, the radio program and the book exchange— the embryo for Lugar Común?

LY: Let’s say it was like a training camp and an apprenticeship, since thanks to the work of literary promotion and the editing of digital content, we established a cordial relationship with a group of fiction writers, poets, essayists, critics, journalists, designers, editors and photographers, all of them from the world of reading and writing. Without realizing it, we were preparing ourselves for the editorial work of Lugar Común, since those years also gave us the chance to measure the pulse of what was being written and read in Venezuela.

In what year did the publishing house begin?

LY: Editorial Lugar Común (which changed its name in the middle of 2014 to Libros Lugar Común), is born in 2011, with the publication of the novel El libro de Esther, by Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez.

Who works for the publishing house?

LY: At the moment, those of us who make up the direction and operation of Libros Lugar Común are Rodrigo Blanco and myself, along with a team of people who participate as collaborators, among them Patricia Heredia, who has been with us at the publishing house for more than two years.

From your beginnings to last year, are there significant changes in Venezuela’s publishing field? What might those changes be?

RB: We think many things have changed. In the last three years we’ve seen how, on the one hand, the contraction of the Venezuelan publishing market has increased. Transnational companies like Random House and Alfaguara have left Venezuela. The already existing publishing houses began to suffer the blows of the paper shortage that considerably diminished production in 2013 and part of 2014.

On the other hand, during this same period of crisis we’ve witnessed the emergence of small, independent publishing houses who have come to do the work that was left behind by the transnational companies. And that’s a positive response to the crisis. Towards the second semester of 2014, the rhythm of publications seemed to recuperate, but not without an enormous cost: we’re referring, literally, to the increase in the price of books due to high production costs.

You mention the Venezuelan publishing houses that have emerged in recent years, such as Ígneo, Alhilo Editorial, Utopía Editorial and Negro Sobre Blanco, among others. With the absence of the transnationals and the increased price of books, did Venezuelan literature become a good business? Or, did it become the only means of doing business?

LY: At Libros Lugar Común we don’t think of literature exclusively as a business. It’s true that we believe in the profitability of books and authors, but above all we trust the quality of the product. And if the product is good, there are reasons for trusting that sales will go well. But very few editors dedicate themselves to this work with the idea of becoming millionaires. Making books isn’t a buoyant business, much less at this time, in this country. It’s a bold business that’s worth the risks.

At the moment, the impulse to write seems to be very high in Venezuela. There’s a growing desire to express ideas, emotions, experiences, and to materialize that desire in books. The complex reality we live stimulates writing and reading (although not at the level that certain enthusiasts would have us believe). In that sense, the publishing houses have a very demanding task of selection, investment and production, in order to guarantee the balance between the value and the price of a book, notions that are often confused in the publishing market.

If making books isn’t a “buoyant business,” why keep printing them? For the love of art?

RB: I do think there are actual possibilities for the book business to become a sustainable endeavor and at the same time that it might contribute to the cultural heritage of a country. Why keep doing it? For the love of art and because we still believe in that possibility.

For an independent publishing house in the current context, how many copies should be printed for each edition of your titles? And, of that number, how many copies do you need to sell in order to maintain a minimum margin of recovery and profit?

LY: We live subordinated to an economy that makes any budget volatile. Each week the costs of production and distribution rise. It’s nearly impossible to maintain a business plan that doesn’t feel threatened by a gelatinous and restrictive economy. Which means that internal administration plays a fundamental role.

The number of each of our titles tends to be 1,000 copies, except for the poetry collection which is 500 copies. In order to cover the production costs, we have to sell from 40% to 50% of the copies of each book.

What are the three books you’ve published that have been reprinted the most?

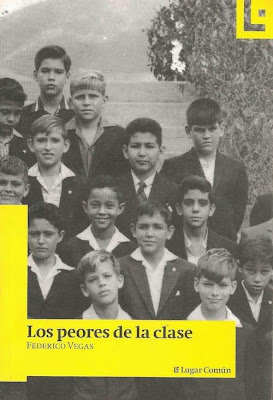

RB: The children’s book Ratón y vampiro, written by Yolanda Pantin and illustrated by Jefferson Quintana; El libro de Esther by Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez; and Los peores de la clase by Federico Vegas.

In regards to distribution, what do you think of applications like Kindle in the U.S. or Librero ETC in Venezuela? Do you distribute your titles through these platforms? Why or why not?

LY: Any project that contributes to disseminating the titles from our catalog is of course welcome, as long as the distribution agreements benefit both parties. We’re not against digital platforms. On the contrary, the more platforms we have for reading, the more visibility the publishing house, its books and its authors gain. Several books by Lugar Común are already available at the platform Librero ETC.

What books will you publish in 2015? Can you give us a preview of the project El bravo tuki by Jesús Torrivilla and Juan Pedro Cámara?

RB: Because of Venezuela’s situation, it’s difficult for us to anticipate the titles for this year. So we’d rather only mention the ones that are definite for this current four-month period. Those are Ogros ejemplares, by Daniel Centeno, and El bravo tuky, by Torrivilla y Cámara.

Centeno’s book is a compilation coordinated by the journalist Oscar Medina of the artist profiles that Daniel Centeno has been publishing periodically in the magazine Sala de Espera. It’s a compendium of exotic lives, narrated with the rigorousness of good journalism and the plastic expressiveness of a writer like Daniel Centeno, who will surprise readers with this book.

El bravo tuky is, simply, one of the books we’ve most enjoyed reading at the publishing house. It’s the first and up until this point the only serious study (without being boring) of the tuky phenomenon. The work of Jesús Torrivilla and Juan Pedro Cámara combines an academic register of the origins of industrial music, along with journalistic and testimonial work on the protagonists of the tuky musical movement. It’s a book that could have an important impact on the circle of publications about music, postmodernism and cultural studies.

The publishing house is part of Lugar Común Bookstore, located in Caracas. Besides selling books, you also facilitate literary workshops, along with conferences and the presentation of musical groups. Have you considered taking this extra-literary experience of Lugar Común to another city?

RB: Actually, it’s the other way around: at the beginning, the bookstore formed part of the publishing house. At least, that’s how it was first conceived. The publishing house was created in 2011 and the bookstore was inaugurated and joined the Lugar Común project in December of 2013. Now the publishing house and bookstore proceed independently.

{ Hensli Rahn Solórzano, Contrapunto, 7 February 2015 }

[Rodrigo Blanco and Luis Yslas, by Carlos Ancheta]

Within a few years, the publishing house Lugar Común has become a point of reference on Venezuelan bookshelves. Contrapunto spoke with the two writers who run the publishing house, Rodrigo Blanco and Luis Yslas.

Hensli Rahn Solórzano.- Blame it on the Venezuelan novelist Francisco “Pancho” Massiani. One afternoon, two graduates of the School of Letters at the Central University of Venezuela, the editor Luis Yslas and the young UCV professor Rodrigo Blanco, coincided at his house.

The common goals shared by this pair moved them to take on the project ReLectura, a type of lab or “training camp” that would help them in the eventual foundation of the publishing house that concerns us today: Libros Lugar Común [Commonplace Books].

“After an exchange of possible names, we were tired and eventually everything we suggested was commonplace,” recalls the writer Luis Yslas about their name. “I thought that could be the name, understanding it as a space for gathering in a common space, of similar interests... playing with the double meaning of the phrase.”

In 2013, Yslas and Blanco, along with other associates, opened the Lugar Común Bookstore in the east side of Caracas. The establishment very soon became a stage for musical groups, a classroom for literary workshops and a space for presenting new books. This is how the “Lugarcomunistas” made a name for themselves in Caracas.

However, “now the publishing house and bookstore proceed independently,” clarifies Rodrigo Blanco, the author of three collections of short stories and an unpublished novel.

Since its foundation until today, Libros Lugar Común has been a witness to the passing of time and the changes being generated in Venezuela. In their own words, they have passed through the contraction of the editorial market in 2012, the paper shortage crisis of 2013-2014, and the devaluations of the bolivar that now affect the price of books. What follows is the rest of the story as told to Contrapunto by the founders of the publishing house.

How did you both meet and how did you decide to start the project ReLectura in 2007?

LY: We coincided one afternoon at Pancho Massiani’s house. From then on, we shared conversations, affinities as readers, beers at the local Chinese restaurants (our first and improvised operation headquarters). Two years later, the novelist Federico Vegas invited us to participate in a project he had in mind. He wanted to promote encounters between readers and writers, by means of gatherings, readings, book exchanges, and also through a webpage that ended up becoming a type of literary magazine. That’s how ReLectura emerged.

Is ReLectura —the webpage, the radio program and the book exchange— the embryo for Lugar Común?

LY: Let’s say it was like a training camp and an apprenticeship, since thanks to the work of literary promotion and the editing of digital content, we established a cordial relationship with a group of fiction writers, poets, essayists, critics, journalists, designers, editors and photographers, all of them from the world of reading and writing. Without realizing it, we were preparing ourselves for the editorial work of Lugar Común, since those years also gave us the chance to measure the pulse of what was being written and read in Venezuela.

In what year did the publishing house begin?

LY: Editorial Lugar Común (which changed its name in the middle of 2014 to Libros Lugar Común), is born in 2011, with the publication of the novel El libro de Esther, by Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez.

Who works for the publishing house?

LY: At the moment, those of us who make up the direction and operation of Libros Lugar Común are Rodrigo Blanco and myself, along with a team of people who participate as collaborators, among them Patricia Heredia, who has been with us at the publishing house for more than two years.

From your beginnings to last year, are there significant changes in Venezuela’s publishing field? What might those changes be?

RB: We think many things have changed. In the last three years we’ve seen how, on the one hand, the contraction of the Venezuelan publishing market has increased. Transnational companies like Random House and Alfaguara have left Venezuela. The already existing publishing houses began to suffer the blows of the paper shortage that considerably diminished production in 2013 and part of 2014.

On the other hand, during this same period of crisis we’ve witnessed the emergence of small, independent publishing houses who have come to do the work that was left behind by the transnational companies. And that’s a positive response to the crisis. Towards the second semester of 2014, the rhythm of publications seemed to recuperate, but not without an enormous cost: we’re referring, literally, to the increase in the price of books due to high production costs.

You mention the Venezuelan publishing houses that have emerged in recent years, such as Ígneo, Alhilo Editorial, Utopía Editorial and Negro Sobre Blanco, among others. With the absence of the transnationals and the increased price of books, did Venezuelan literature become a good business? Or, did it become the only means of doing business?

LY: At Libros Lugar Común we don’t think of literature exclusively as a business. It’s true that we believe in the profitability of books and authors, but above all we trust the quality of the product. And if the product is good, there are reasons for trusting that sales will go well. But very few editors dedicate themselves to this work with the idea of becoming millionaires. Making books isn’t a buoyant business, much less at this time, in this country. It’s a bold business that’s worth the risks.

At the moment, the impulse to write seems to be very high in Venezuela. There’s a growing desire to express ideas, emotions, experiences, and to materialize that desire in books. The complex reality we live stimulates writing and reading (although not at the level that certain enthusiasts would have us believe). In that sense, the publishing houses have a very demanding task of selection, investment and production, in order to guarantee the balance between the value and the price of a book, notions that are often confused in the publishing market.

If making books isn’t a “buoyant business,” why keep printing them? For the love of art?

RB: I do think there are actual possibilities for the book business to become a sustainable endeavor and at the same time that it might contribute to the cultural heritage of a country. Why keep doing it? For the love of art and because we still believe in that possibility.

For an independent publishing house in the current context, how many copies should be printed for each edition of your titles? And, of that number, how many copies do you need to sell in order to maintain a minimum margin of recovery and profit?

LY: We live subordinated to an economy that makes any budget volatile. Each week the costs of production and distribution rise. It’s nearly impossible to maintain a business plan that doesn’t feel threatened by a gelatinous and restrictive economy. Which means that internal administration plays a fundamental role.

The number of each of our titles tends to be 1,000 copies, except for the poetry collection which is 500 copies. In order to cover the production costs, we have to sell from 40% to 50% of the copies of each book.

What are the three books you’ve published that have been reprinted the most?

RB: The children’s book Ratón y vampiro, written by Yolanda Pantin and illustrated by Jefferson Quintana; El libro de Esther by Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez; and Los peores de la clase by Federico Vegas.

In regards to distribution, what do you think of applications like Kindle in the U.S. or Librero ETC in Venezuela? Do you distribute your titles through these platforms? Why or why not?

LY: Any project that contributes to disseminating the titles from our catalog is of course welcome, as long as the distribution agreements benefit both parties. We’re not against digital platforms. On the contrary, the more platforms we have for reading, the more visibility the publishing house, its books and its authors gain. Several books by Lugar Común are already available at the platform Librero ETC.

What books will you publish in 2015? Can you give us a preview of the project El bravo tuki by Jesús Torrivilla and Juan Pedro Cámara?

RB: Because of Venezuela’s situation, it’s difficult for us to anticipate the titles for this year. So we’d rather only mention the ones that are definite for this current four-month period. Those are Ogros ejemplares, by Daniel Centeno, and El bravo tuky, by Torrivilla y Cámara.

Centeno’s book is a compilation coordinated by the journalist Oscar Medina of the artist profiles that Daniel Centeno has been publishing periodically in the magazine Sala de Espera. It’s a compendium of exotic lives, narrated with the rigorousness of good journalism and the plastic expressiveness of a writer like Daniel Centeno, who will surprise readers with this book.

El bravo tuky is, simply, one of the books we’ve most enjoyed reading at the publishing house. It’s the first and up until this point the only serious study (without being boring) of the tuky phenomenon. The work of Jesús Torrivilla and Juan Pedro Cámara combines an academic register of the origins of industrial music, along with journalistic and testimonial work on the protagonists of the tuky musical movement. It’s a book that could have an important impact on the circle of publications about music, postmodernism and cultural studies.

The publishing house is part of Lugar Común Bookstore, located in Caracas. Besides selling books, you also facilitate literary workshops, along with conferences and the presentation of musical groups. Have you considered taking this extra-literary experience of Lugar Común to another city?

RB: Actually, it’s the other way around: at the beginning, the bookstore formed part of the publishing house. At least, that’s how it was first conceived. The publishing house was created in 2011 and the bookstore was inaugurated and joined the Lugar Común project in December of 2013. Now the publishing house and bookstore proceed independently.

{ Hensli Rahn Solórzano, Contrapunto, 7 February 2015 }

1.15.2015

Si hay impunidad no hay un coño (o a dónde ir a protestar) / Eduardo Febres

If There’s Impunity We Don’t Have Shit (Or Anywhere to Protest)

[Photo by Eduardo Febres]

1

Was Chávez killed? It’s hard to believe, but the truth is we don’t know. I think that if we find out one day it will be through a declassified file from U.S. intelligence, because the Venezuelan State, as far as we know, hasn’t moved a finger to find out. Nicolás Maduro announced an investigation that if it ever proceeded we never found out about it, and there are people convinced he was killed, just like there’s more people convinced he wasn’t. But in terms of knowing, no one knows.

2

But we do know very well that the indigenous leader from the Yukpa tribe Sabino Romero, who died two days before Chávez, was killed. After many attempts, threats, warnings, gunshots, blood, and above all after a cascade of impunity, they killed him. When he was traveling from Tocuco to Shaktapa, they shot him dead in front of his wife.

And ever since then, impunity continues to drag other corpses to join them.

3

There are five people in jail for complicity with the murder of Sabino, all of them sentenced to seven years, none of them are the killer. The person accused of pulling the trigger, Ángel Romero Bracho, hasn’t been sentenced. And the trial wanders from the table to the dining room. Convened for January 9th, it mobilized a few people at the doors of the Palace of Justice. A handful of people (twenty, thirty people) who are following the process and paying attention to it.

Among other things, because the masterminds (who aren’t clearly pointed out, but we suppose with a great deal of precision and elements that they’re ranchers) still haven’t even been touched by the law.

4

When they arrive at the courthouse they find out there’s no court session. Amidst a muddled and bureaucratic circulation of information, they’re able to find out it had been moved to January 6th, the Día de Reyes holiday and practially an official day off. And in a coincidence that’s quite convenient for paranoia and evil, the street leading to the Palace of Justice was blocked off by security forces. Supposedly because of a graduation (“These motherfuckers are graduating with a degree in corruption,” was overheard).

When they lift the show of force (facing the inoffensive convocation, the suspicious-paranoid version supposes), the protest moves to the Palace, with a bit more intensity.

5

The protest? Nothing extraordinary in how it played out, aside from a few protestors with their faces painted in tribute to the First Peoples: a blocked street, a few hand-held signs, some shouts, proclamations and demands.

What’s extraordinary are the comments overheard, among the passersby on the sidewalk in front of the Palace.

One: “Go back to the east side of Caracas.” A purée dissociated by the State-run TV station VTV, who can’t conceive how a group of people, most of them young, most of them cheerful, most of them pissed off, would protest, demand, shout, express their indignation in the face of impunity, without being opposition protestors.

Sabino is a symbol of impunity, amid a shit storm where thousands of other injustices circulate. And he is a symbol defended with the conviction that Chávez lives, or you don’t defend him at all. As it’s also a conviction one fights for with the knowledge that in those paralyzed, prudish, rigid, aged, ignorant and comfortable sectors of Chavismo, Chávez doesn’t live.

Another: “Why are these people protesting such a stupid thing, if I just spent four hours today in a food line.” This one not as much of a purée but equally dissociated, by TV but also by his own misery (the inner TV), who can’t put the two neurons together he needs to understand that as long as there’s impunity there won’t be shit anywhere. Not for him and his selfishness, not for anyone.

6

The poor street vendor who thinks it’s fair to exploit the poor (and his likeness, his brother, the poor man who buys from him); the National Guard who smuggles one, two, three, one hundred thousand kilos of whatever (and his likeness, his brother, the narco or the smuggler who sets up the deal), the exploiter of the dollar exchange system, who looted until the only thing left were empty containers (and his likeness, his brother, the casual exploiter of the system, who takes a few crumbs through his credit card), as well as whoever kills, rapes, steals or tortures. They could all fit in that place, facing those who fight for the symbol of Sabino.

This place is an accomplice and artifice to all of them. This is where all the food lines could end, all the empty shelves, all the massacres, the cases like Simonovis, Afiuni, Danilo Anderson along with some type of answer as to why it sometimes seems like the government wants to and can’t.

This is where the cancer, as well, could end.

{ Eduardo Febres, Contrapunto, 14 January 2015 }

[Photo by Eduardo Febres]

1

Was Chávez killed? It’s hard to believe, but the truth is we don’t know. I think that if we find out one day it will be through a declassified file from U.S. intelligence, because the Venezuelan State, as far as we know, hasn’t moved a finger to find out. Nicolás Maduro announced an investigation that if it ever proceeded we never found out about it, and there are people convinced he was killed, just like there’s more people convinced he wasn’t. But in terms of knowing, no one knows.

2

But we do know very well that the indigenous leader from the Yukpa tribe Sabino Romero, who died two days before Chávez, was killed. After many attempts, threats, warnings, gunshots, blood, and above all after a cascade of impunity, they killed him. When he was traveling from Tocuco to Shaktapa, they shot him dead in front of his wife.

And ever since then, impunity continues to drag other corpses to join them.

3

There are five people in jail for complicity with the murder of Sabino, all of them sentenced to seven years, none of them are the killer. The person accused of pulling the trigger, Ángel Romero Bracho, hasn’t been sentenced. And the trial wanders from the table to the dining room. Convened for January 9th, it mobilized a few people at the doors of the Palace of Justice. A handful of people (twenty, thirty people) who are following the process and paying attention to it.

Among other things, because the masterminds (who aren’t clearly pointed out, but we suppose with a great deal of precision and elements that they’re ranchers) still haven’t even been touched by the law.

4

When they arrive at the courthouse they find out there’s no court session. Amidst a muddled and bureaucratic circulation of information, they’re able to find out it had been moved to January 6th, the Día de Reyes holiday and practially an official day off. And in a coincidence that’s quite convenient for paranoia and evil, the street leading to the Palace of Justice was blocked off by security forces. Supposedly because of a graduation (“These motherfuckers are graduating with a degree in corruption,” was overheard).

When they lift the show of force (facing the inoffensive convocation, the suspicious-paranoid version supposes), the protest moves to the Palace, with a bit more intensity.

5

The protest? Nothing extraordinary in how it played out, aside from a few protestors with their faces painted in tribute to the First Peoples: a blocked street, a few hand-held signs, some shouts, proclamations and demands.

What’s extraordinary are the comments overheard, among the passersby on the sidewalk in front of the Palace.

One: “Go back to the east side of Caracas.” A purée dissociated by the State-run TV station VTV, who can’t conceive how a group of people, most of them young, most of them cheerful, most of them pissed off, would protest, demand, shout, express their indignation in the face of impunity, without being opposition protestors.

Sabino is a symbol of impunity, amid a shit storm where thousands of other injustices circulate. And he is a symbol defended with the conviction that Chávez lives, or you don’t defend him at all. As it’s also a conviction one fights for with the knowledge that in those paralyzed, prudish, rigid, aged, ignorant and comfortable sectors of Chavismo, Chávez doesn’t live.

Another: “Why are these people protesting such a stupid thing, if I just spent four hours today in a food line.” This one not as much of a purée but equally dissociated, by TV but also by his own misery (the inner TV), who can’t put the two neurons together he needs to understand that as long as there’s impunity there won’t be shit anywhere. Not for him and his selfishness, not for anyone.

6

The poor street vendor who thinks it’s fair to exploit the poor (and his likeness, his brother, the poor man who buys from him); the National Guard who smuggles one, two, three, one hundred thousand kilos of whatever (and his likeness, his brother, the narco or the smuggler who sets up the deal), the exploiter of the dollar exchange system, who looted until the only thing left were empty containers (and his likeness, his brother, the casual exploiter of the system, who takes a few crumbs through his credit card), as well as whoever kills, rapes, steals or tortures. They could all fit in that place, facing those who fight for the symbol of Sabino.

This place is an accomplice and artifice to all of them. This is where all the food lines could end, all the empty shelves, all the massacres, the cases like Simonovis, Afiuni, Danilo Anderson along with some type of answer as to why it sometimes seems like the government wants to and can’t.

This is where the cancer, as well, could end.

{ Eduardo Febres, Contrapunto, 14 January 2015 }

11.19.2014

Victoria de Stefano: “Vivimos con temor a que el país nos arrastre” / Hugo Prieto

Victoria de Stefano: “We live in fear of the country sweeping us away”

[Photo: Elvira Prieto]

The writer is struggling with the novel she’s writing at the moment. She has chosen a Gauguin painting as a lamp that guides her path... Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Surely the country, the bog that Rómulo Gallegos spoke of, is imposing formidable obstacles for her. But we already know about her tenacity, her perseverance. There will be continuity, a line that extends to her most recent novel Paleografías (2011), but also a portrait of what we are and a renewed exploration, perhaps without the joy of other experiences, of that great theme which is desolation nearly transformed into a literary genre.

Victoria de Stefano will speak about the contemplative world, which is the world of artists and of intellectuals in general, and about her extensive literary oeuvre at the Plaza Altamira Book Fair tonight. She will be joined by another great Venezuelan writer, Elisa Lerner, in a colloquium that will be moderated by the poet Rafael Castillo Zapata. The event is scheduled for 6:00 P.M. What follows is a long conversation with the author of Historias de la marcha a pie (1997).

What’s your view of the panorama of Venezuelan literature?

I think that the crisis of these last few years (economic, political, cultural...) the crisis of a country more that divided, right? even with people completely cut off from one another, has forced everyone to feel the necessity of reading Venezuelan writers. In the 1970s, when I began to appear as a writer, let’s say, there were very few writers, apart from the already famous ones: Adriano González León, Salvador Garmendia, Elisa Lerner, Baica Dávalos, Orlando Araujo, Francisco Masiani... I could name more, but there wasn’t the quantity of writers from different generations who coexist as they do today. I’m talking about fiction, about the novel, the short story. Of course, there’s also the poets. In those years, young Venezuelan writers needed to read the elders. Now I think we read each other more. Today I have no problem reading both younger and older writers. There’s a need for acknowledgement and also, perhaps, for establishing a tradition.

That seems to come later in Venezuela, right? That is, if there’s not a tradition, there’s not a school, there isn’t constant renovation but rather a literature like the one we’ve seen: zigzagging, abrupt.

But we definitely can say that the academy has grown, the professors have grown. We can’t talk about literary critics, since there aren’t any publications where literary critics might write. I mean, the tradition of criticism is weaker, but we do have one. What I think is that there’s been an attempt to remake a tradition.

With the existence of talent, isn’t there a need for that literary tradition, that tradition of criticism?

There is a literary tradition! That is, there’s been a tendency in the country to depend on tradition. In Argentine literature, for example, where that fact is very present, there’s something interesting as well. There are even writers who in their novels make references to not only literary tradition, but they embody it in characters, in situations, in circumstances. There’s a type of dialogue with other writers, with other tendencies. We’ve seen much less of that process, but the tradition exists. We’re not going to say that it’s a tradition like the French one or what Gombrowicz calls the primary traditions. No. We still belong to the secondary traditions.

Does that make you uncomfortable? Does it make you perceive a more precarious reality?

No, more conflictive for the writer. I mean, if the writer is reduced to the local world, to the Venezuelan tradition —which of course is part of the Latin American tradition, right?—, if you localize yourself too much, you lose the possibility of creating beyond those immediate surroundings and if you turn too much to the outside, in regards to writers from abroad, that also turns you into a second rate writer. I’m going to lay it out for you as a writer not a critic, because the question you ask me about the panorama would imply that I’ve tried to internalize that panorama, something I haven’t done. I’ve never been a professor of Venezuelan or Latin American literature. What is the conflict one faces? Well, in the end I say to myself, I’m going to write what I want, what I can and what interests me, no matter how much the country might scold me for not writing about what’s happening here, regardless of someone telling me I have a lot of references to Italy in my work. Yes, those are in there.

To traditions outside our own?

We all have the right to do that. The homeland, for writers, for intellectuals in general, can’t be reduced to geographical limits. That theme of identity no longer interests me at all. That was back in the 1970s, not just for me but for many writers. Well, trying to write proudly, to write what you think has to be written. There’s a detail too. I was born in 1940, in Rimel, Italy. When the war was over, I came to Venezuela. There’s a glance, because I have a family tradition, both my father and my mother were educated, trained people. So, how am I expected to cut that world off? I can’t. Anyways, today we’re all multicultural beings.

Venezuela is a country that’s eternally under construction, that has struggled a great deal in many areas to achieve accomplishments, completed tasks. Could its literature be a reflection of that?

Each generation, each period, tries to build itself from the beginning, as if what came before weren’t there. The generation I belong to studied elementary school in the 1950s, I entered the university in 1958, we had a more vernacular education compared to students today. I say it in a more Venezulanist, more Americanist sense. When I started school, we had many professors who came from Argentina, some of them came after the fall of Perón, we used to read the poetry of Gabriela Mistral. Do they read anything like that in high school today? We read Ramón Díaz Sánchez very well. I used to levitate with “Cumboto,” With the novels of José Rafael Pocaterra. It was actually a world with a more Latin Americanist vision.

I’d like to propose something to you, since you mention Pocaterra. Many people are waiting for the novel about the Bolivarian revolution, like Memories of Underdevelopment in Cuba or the counter narrative, as Memorias de un venezolano en la decadencia could have been. But neither of them has appeared.

But that’s a petition that can’t be made to writers. I mean, Pocaterra’s book has to do with the concrete experiences of a country, it’s the biography of a writer, a writer who’s been in jail, who has known conspiracies, who also has a lineage and antecedents in England, he forms part of a time period when politics, the country and literature went practically hand in hand. The role of the writer now isn't Pocaterra’s, nor is it Arturo Uslar Pietri’s. They're more isolated figures, they’re less engaged with the country in that sense. By this I mean the country has become departmentalized, just like in France today you can’t think of figures such as Sartre or Albert Camus, it’s another era, another story, another world.

They’re more solitary, more self-absorbed.

It’s another society. That starring role no longer exists and whoever aspires to it might attain some social or media success, but it won’t go beyond that. We write, and who knows if in 20 or 30 years anyone will read us or not. I think the idea is that writers should write, regardless of whether they might hope or not hope to be read. What will be left of this small world in 20 or 30 years? We don’t know.

What’s left of that country from your first novel El desolvido (1970)?

A great disenchantment and a great sadness. But there might also be a certain nostalgia for youth, for the chimeras and the experiences that were lived and took shape.

Bitterness?

No, not bitterness.

It’s nostalgia, a sorrowful feeling, a certain mourning, but not bitterness.

It includes a portrait of your generation.

Yes. Historias de la marcha a pie, which I wrote much later on and was very difficult to publish, is a continuation of La noche llama a la noche (1985), it’s another reflection on the same theme, amplified. In the tradition of universal literature, the theme of disenchantment is very present, there’s even a category of novels called the category of disenchantment and in Cuban literature there are great novels of disenchantment, for example, the novels of Jesús Díaz. There’s a tradition, it almost constitutes a genre. But when I write, I don’t do it based on a plan... I’ll write about this... I’ll write about that, no. I start writing from very small things. For example, in Cabo de vida (1993), which is a novel that hasn’t been read much, because it didn’t have editorial continuity, the theme is a group of waiters for a party planning agency, who go from party to party, serving, so there’s both worlds, how they see them and the fact that being waiters doesn’t prevent them from having a spiritual rather than an intellectual life.

Out of those utopias, those experiences, what remains? What line could be established in continuity?

I wouldn’t know how to answer what line of continuity might exist. There are people who lived through those experiences, some of them are writers, some are intellectuals, some are even in politics and have lived through the fact of disenchantment. Sometimes, a few of them can do this with bitterness, others not. I don’t feel any bitterness.

The characters in your novels live in surroundings that dominate them, that impose themselves, but at the same time they’re characters that reflect tremendously about that. One could say they’re not people of action and yet they experience situations of great adversity.

The theme of adversity is present in my novels. In La noche llama a la noche, there’s a man of action, who is the kidnapper, then he leaves and continues his political activities throughout the world. He dies on a train. We don’t know how, I don’t even know how, if it’s a suicide or a paranoid situation that leads to his death. In my novels there’s a reflection on action and on the contemplative world, which is the world of the artist. That’s in all my novels. Even in the one I’m currently writing. But there’s an overarching theme which is adversity. Maybe when you asked me if there’s bitterness, I said no, but there is a great fear of adversity. Of the adversity that can present itself in different ways. There’s also the theme of freedom and of how you’re determined, how others determine you, and of what the human being’s space for freedom might be. As a question. I never have an answer.

Adversity isn’t the result of an action, it’s the result of a circumstance, of events that are unleashed and those characters are unrelated to those events.

And that’s our reality, for my characters. I don’t know if I’m making sense. My characters include many depressed people, who are living through a moment of crisis. Some of them very serious, others not as much. I don’t know how a French person might live in Paris, who’s a professor or writes. But I do know how we live here in Venezuela. Those of us who are intellectuals, writers, even other types of people, we live everything as if it were a crisis, with a fear of a certain adversity, that the country might overtake us, that it might sweep us away, that we might return, as Rómulo Gallegos would say, to the bog. I do think that’s present and, surely, it can be found in many other writers.

There’s an anguish that competes with adversity. One notices that the country already devoured us and it continues to do so. How can we fight against that?

As an individual, independent from your social or intellectual condition, we all have to fight against that, individually.

With an intellectual life or a political one?

Each person makes a choice. Some are made for political life and they fight from there. Others are made for the spiritual life. Regardless, they’re not two separate things, right? Are they two separate things?

I think that in Venezuela, yes.

Ah then, in Venezuela yes.

Would you agree with that?

Yes, I agree.

Is Historias de la marcha a pie a novel about death?

It’s about illness, death, adversities. Yes, that’s the central theme. On one occasion I read a chapter at a university in Mexico, where I was invited. At first I said I felt bad with them, for reading such a terrible chapter to them. And the professor who invited me, who knew my novel very well, said: “But it’s written in such a jubilant style. One feels that when the writer writes she enters into a certain ecstasy, a certain jubilation, so read it like that.”

It’s also a jubilation for life.

Of course, exactly. That’s what he meant.

It has that counterpoint.

That’s life.

And what you’re narrating is death.

Which is a part of life.

Don’t you think death is a business we should leave to doctors, priests, conjurers?

I think that regardless of the word business, each one of us negotiates with our illness and our death, in our own way. There are people who don’t negotiate illness and death. I’m remembering a friend who was gravelly ill and the doctors told him he needed an operation and he didn’t do it. He died on his own terms.

Which is also valid.

Perfectly valid. Juan Sánchez Peláez [the poet] also refused treatment. But regardless of that, maybe recovery by means of medicine is valid. But there’s also recovery through desire, through necessity, through will. All the variations exist. So does suicide. At the moment, I’m writing a novel. Each time I write a novel, I set up a painting for myself. It’s as if it guides me, maybe it doesn’t guide me and I find another one. But the one I have for my novel right now, which I’m having a lot of trouble writing, I think I feel a certain amount of dejection. Where am I heading? What am I writing? What interest can this have? I’m not writing with the jubilation I had when I wrote Historias de la marcha a pie. Does that have to do with what’s happening in Venezuela? I suppose. Obviously yes. But the painting I set up is Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Do you know which one it is? The famous painting by Gauguin that he painted in one of those islands.

In that sense, will your next novel have continuity with Paleografías?

I hope so. But I feel that what we’re living is slightly where we come from, who we are, where we’re going and that it’s an eternal question and that maybe with us it’s more present, marked.

It’s an eternal question, but at this moment, for us in Venezuela, it’s an urgent question.

Well, eternal and urgent.

{ Hugo Prieto, Contrapunto, 16 November 2014 }

[Photo: Elvira Prieto]

The writer is struggling with the novel she’s writing at the moment. She has chosen a Gauguin painting as a lamp that guides her path... Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Surely the country, the bog that Rómulo Gallegos spoke of, is imposing formidable obstacles for her. But we already know about her tenacity, her perseverance. There will be continuity, a line that extends to her most recent novel Paleografías (2011), but also a portrait of what we are and a renewed exploration, perhaps without the joy of other experiences, of that great theme which is desolation nearly transformed into a literary genre.

Victoria de Stefano will speak about the contemplative world, which is the world of artists and of intellectuals in general, and about her extensive literary oeuvre at the Plaza Altamira Book Fair tonight. She will be joined by another great Venezuelan writer, Elisa Lerner, in a colloquium that will be moderated by the poet Rafael Castillo Zapata. The event is scheduled for 6:00 P.M. What follows is a long conversation with the author of Historias de la marcha a pie (1997).

What’s your view of the panorama of Venezuelan literature?

I think that the crisis of these last few years (economic, political, cultural...) the crisis of a country more that divided, right? even with people completely cut off from one another, has forced everyone to feel the necessity of reading Venezuelan writers. In the 1970s, when I began to appear as a writer, let’s say, there were very few writers, apart from the already famous ones: Adriano González León, Salvador Garmendia, Elisa Lerner, Baica Dávalos, Orlando Araujo, Francisco Masiani... I could name more, but there wasn’t the quantity of writers from different generations who coexist as they do today. I’m talking about fiction, about the novel, the short story. Of course, there’s also the poets. In those years, young Venezuelan writers needed to read the elders. Now I think we read each other more. Today I have no problem reading both younger and older writers. There’s a need for acknowledgement and also, perhaps, for establishing a tradition.

That seems to come later in Venezuela, right? That is, if there’s not a tradition, there’s not a school, there isn’t constant renovation but rather a literature like the one we’ve seen: zigzagging, abrupt.

But we definitely can say that the academy has grown, the professors have grown. We can’t talk about literary critics, since there aren’t any publications where literary critics might write. I mean, the tradition of criticism is weaker, but we do have one. What I think is that there’s been an attempt to remake a tradition.

With the existence of talent, isn’t there a need for that literary tradition, that tradition of criticism?

There is a literary tradition! That is, there’s been a tendency in the country to depend on tradition. In Argentine literature, for example, where that fact is very present, there’s something interesting as well. There are even writers who in their novels make references to not only literary tradition, but they embody it in characters, in situations, in circumstances. There’s a type of dialogue with other writers, with other tendencies. We’ve seen much less of that process, but the tradition exists. We’re not going to say that it’s a tradition like the French one or what Gombrowicz calls the primary traditions. No. We still belong to the secondary traditions.

Does that make you uncomfortable? Does it make you perceive a more precarious reality?

No, more conflictive for the writer. I mean, if the writer is reduced to the local world, to the Venezuelan tradition —which of course is part of the Latin American tradition, right?—, if you localize yourself too much, you lose the possibility of creating beyond those immediate surroundings and if you turn too much to the outside, in regards to writers from abroad, that also turns you into a second rate writer. I’m going to lay it out for you as a writer not a critic, because the question you ask me about the panorama would imply that I’ve tried to internalize that panorama, something I haven’t done. I’ve never been a professor of Venezuelan or Latin American literature. What is the conflict one faces? Well, in the end I say to myself, I’m going to write what I want, what I can and what interests me, no matter how much the country might scold me for not writing about what’s happening here, regardless of someone telling me I have a lot of references to Italy in my work. Yes, those are in there.

To traditions outside our own?

We all have the right to do that. The homeland, for writers, for intellectuals in general, can’t be reduced to geographical limits. That theme of identity no longer interests me at all. That was back in the 1970s, not just for me but for many writers. Well, trying to write proudly, to write what you think has to be written. There’s a detail too. I was born in 1940, in Rimel, Italy. When the war was over, I came to Venezuela. There’s a glance, because I have a family tradition, both my father and my mother were educated, trained people. So, how am I expected to cut that world off? I can’t. Anyways, today we’re all multicultural beings.

Venezuela is a country that’s eternally under construction, that has struggled a great deal in many areas to achieve accomplishments, completed tasks. Could its literature be a reflection of that?

Each generation, each period, tries to build itself from the beginning, as if what came before weren’t there. The generation I belong to studied elementary school in the 1950s, I entered the university in 1958, we had a more vernacular education compared to students today. I say it in a more Venezulanist, more Americanist sense. When I started school, we had many professors who came from Argentina, some of them came after the fall of Perón, we used to read the poetry of Gabriela Mistral. Do they read anything like that in high school today? We read Ramón Díaz Sánchez very well. I used to levitate with “Cumboto,” With the novels of José Rafael Pocaterra. It was actually a world with a more Latin Americanist vision.

I’d like to propose something to you, since you mention Pocaterra. Many people are waiting for the novel about the Bolivarian revolution, like Memories of Underdevelopment in Cuba or the counter narrative, as Memorias de un venezolano en la decadencia could have been. But neither of them has appeared.

But that’s a petition that can’t be made to writers. I mean, Pocaterra’s book has to do with the concrete experiences of a country, it’s the biography of a writer, a writer who’s been in jail, who has known conspiracies, who also has a lineage and antecedents in England, he forms part of a time period when politics, the country and literature went practically hand in hand. The role of the writer now isn't Pocaterra’s, nor is it Arturo Uslar Pietri’s. They're more isolated figures, they’re less engaged with the country in that sense. By this I mean the country has become departmentalized, just like in France today you can’t think of figures such as Sartre or Albert Camus, it’s another era, another story, another world.

They’re more solitary, more self-absorbed.

It’s another society. That starring role no longer exists and whoever aspires to it might attain some social or media success, but it won’t go beyond that. We write, and who knows if in 20 or 30 years anyone will read us or not. I think the idea is that writers should write, regardless of whether they might hope or not hope to be read. What will be left of this small world in 20 or 30 years? We don’t know.

What’s left of that country from your first novel El desolvido (1970)?

A great disenchantment and a great sadness. But there might also be a certain nostalgia for youth, for the chimeras and the experiences that were lived and took shape.

Bitterness?

No, not bitterness.

It’s nostalgia, a sorrowful feeling, a certain mourning, but not bitterness.

It includes a portrait of your generation.

Yes. Historias de la marcha a pie, which I wrote much later on and was very difficult to publish, is a continuation of La noche llama a la noche (1985), it’s another reflection on the same theme, amplified. In the tradition of universal literature, the theme of disenchantment is very present, there’s even a category of novels called the category of disenchantment and in Cuban literature there are great novels of disenchantment, for example, the novels of Jesús Díaz. There’s a tradition, it almost constitutes a genre. But when I write, I don’t do it based on a plan... I’ll write about this... I’ll write about that, no. I start writing from very small things. For example, in Cabo de vida (1993), which is a novel that hasn’t been read much, because it didn’t have editorial continuity, the theme is a group of waiters for a party planning agency, who go from party to party, serving, so there’s both worlds, how they see them and the fact that being waiters doesn’t prevent them from having a spiritual rather than an intellectual life.

Out of those utopias, those experiences, what remains? What line could be established in continuity?

I wouldn’t know how to answer what line of continuity might exist. There are people who lived through those experiences, some of them are writers, some are intellectuals, some are even in politics and have lived through the fact of disenchantment. Sometimes, a few of them can do this with bitterness, others not. I don’t feel any bitterness.

The characters in your novels live in surroundings that dominate them, that impose themselves, but at the same time they’re characters that reflect tremendously about that. One could say they’re not people of action and yet they experience situations of great adversity.

The theme of adversity is present in my novels. In La noche llama a la noche, there’s a man of action, who is the kidnapper, then he leaves and continues his political activities throughout the world. He dies on a train. We don’t know how, I don’t even know how, if it’s a suicide or a paranoid situation that leads to his death. In my novels there’s a reflection on action and on the contemplative world, which is the world of the artist. That’s in all my novels. Even in the one I’m currently writing. But there’s an overarching theme which is adversity. Maybe when you asked me if there’s bitterness, I said no, but there is a great fear of adversity. Of the adversity that can present itself in different ways. There’s also the theme of freedom and of how you’re determined, how others determine you, and of what the human being’s space for freedom might be. As a question. I never have an answer.

Adversity isn’t the result of an action, it’s the result of a circumstance, of events that are unleashed and those characters are unrelated to those events.

And that’s our reality, for my characters. I don’t know if I’m making sense. My characters include many depressed people, who are living through a moment of crisis. Some of them very serious, others not as much. I don’t know how a French person might live in Paris, who’s a professor or writes. But I do know how we live here in Venezuela. Those of us who are intellectuals, writers, even other types of people, we live everything as if it were a crisis, with a fear of a certain adversity, that the country might overtake us, that it might sweep us away, that we might return, as Rómulo Gallegos would say, to the bog. I do think that’s present and, surely, it can be found in many other writers.

There’s an anguish that competes with adversity. One notices that the country already devoured us and it continues to do so. How can we fight against that?

As an individual, independent from your social or intellectual condition, we all have to fight against that, individually.

With an intellectual life or a political one?

Each person makes a choice. Some are made for political life and they fight from there. Others are made for the spiritual life. Regardless, they’re not two separate things, right? Are they two separate things?

I think that in Venezuela, yes.

Ah then, in Venezuela yes.

Would you agree with that?

Yes, I agree.

Is Historias de la marcha a pie a novel about death?

It’s about illness, death, adversities. Yes, that’s the central theme. On one occasion I read a chapter at a university in Mexico, where I was invited. At first I said I felt bad with them, for reading such a terrible chapter to them. And the professor who invited me, who knew my novel very well, said: “But it’s written in such a jubilant style. One feels that when the writer writes she enters into a certain ecstasy, a certain jubilation, so read it like that.”

It’s also a jubilation for life.

Of course, exactly. That’s what he meant.

It has that counterpoint.

That’s life.

And what you’re narrating is death.

Which is a part of life.

Don’t you think death is a business we should leave to doctors, priests, conjurers?

I think that regardless of the word business, each one of us negotiates with our illness and our death, in our own way. There are people who don’t negotiate illness and death. I’m remembering a friend who was gravelly ill and the doctors told him he needed an operation and he didn’t do it. He died on his own terms.

Which is also valid.

Perfectly valid. Juan Sánchez Peláez [the poet] also refused treatment. But regardless of that, maybe recovery by means of medicine is valid. But there’s also recovery through desire, through necessity, through will. All the variations exist. So does suicide. At the moment, I’m writing a novel. Each time I write a novel, I set up a painting for myself. It’s as if it guides me, maybe it doesn’t guide me and I find another one. But the one I have for my novel right now, which I’m having a lot of trouble writing, I think I feel a certain amount of dejection. Where am I heading? What am I writing? What interest can this have? I’m not writing with the jubilation I had when I wrote Historias de la marcha a pie. Does that have to do with what’s happening in Venezuela? I suppose. Obviously yes. But the painting I set up is Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Do you know which one it is? The famous painting by Gauguin that he painted in one of those islands.

In that sense, will your next novel have continuity with Paleografías?

I hope so. But I feel that what we’re living is slightly where we come from, who we are, where we’re going and that it’s an eternal question and that maybe with us it’s more present, marked.

It’s an eternal question, but at this moment, for us in Venezuela, it’s an urgent question.

Well, eternal and urgent.

{ Hugo Prieto, Contrapunto, 16 November 2014 }

9.20.2014

Turba nuestra (o el otro bicentenario) / Eduardo Febres

Our Mob (Or, The Other Bicentenary)

[“El Caracazo, 1989” by AVN/Francisco Solórzano]

1

There’s nothing progress and order fears more than the mob. A belligerent force with no visible head that moves with the infinite power of what no longer fears dying. And in Venezuela, a divinity from which saints emanate.

No one prays literally to the mob: one prays to Ismaelito, to Crude Oil, to Isabel the Kid, who didn’t emerge from the mob, but whom the mob of 1989 spread like the rumor of a coup d’état.

As well as the Our Chávez, which is a product of that mob and has been rejected and prayed to.

Routine. Like the poet Dalton said: “When revolution appears on the horizon the old cauldron of religions heats up.”

2

What isn’t prayed for to the mob as an entity, is attributed to it as power. The mob of 1989 is the magma that broke the floor of the country’s old story, to eventually solidify itself as a new narrative landscape. That’s why the anti-Chavista imaginary drools at the possibility that the mob might reappear and break what’s been established by the revolution: because all of that was made with the symbolic capital the mob bequeathed it.

3

Anti-chavismo was wagering on the mob by any means necessary in 2014, and we all know how that turned out. And that’s the possibility that Nicolás Maduro conjures with his so-called Shake-Up (one of the names of the mob) when talking about about political restructuring that fulfills one of Henrique Capriles Radonski’s electoral promises from 2012, to adjust the prices of various regulated products and to announce the imminent increase in the price of gasoline.

Calm down, ladies and gentlemen: there will be no shake-up (no mob), because I’m the one doing the shake-up. No one’s about to come down from the hills because we’re the ones who’ll climb them.

Very clever, but nothing new: the specter of the shake-up has more power in Venezuela than any political party. And nothing explains the economic politics of the Bolivarian revolution (and many other things) better than reading it as an a recurring attempt of that shadow, that seen from a different perspective seems insatiable.

4

In order to invoke the mob, the aristocrat Leopoldo López chose the most forced and least representative milestone of the bicentennial of the first heroic mob: that 12th of February of 1814, when Venezuelan patriots had their only moment of glory against the armies of servants and slaves who, allied with José Tomás Boves, took over the entire country that year (by the way, the same year the government chooses as its emblem, although Hugo Chávez was thinking of something else).