Libros Lugar Común Measures the Pulse of What’s Being Written in Venezuela

[Rodrigo Blanco and Luis Yslas, by Carlos Ancheta]

Within a few years, the publishing house Lugar Común has become a point of reference on Venezuelan bookshelves. Contrapunto spoke with the two writers who run the publishing house, Rodrigo Blanco and Luis Yslas.

Hensli Rahn Solórzano.- Blame it on the Venezuelan novelist Francisco “Pancho” Massiani. One afternoon, two graduates of the School of Letters at the Central University of Venezuela, the editor Luis Yslas and the young UCV professor Rodrigo Blanco, coincided at his house.

The common goals shared by this pair moved them to take on the project ReLectura, a type of lab or “training camp” that would help them in the eventual foundation of the publishing house that concerns us today: Libros Lugar Común [Commonplace Books].

“After an exchange of possible names, we were tired and eventually everything we suggested was commonplace,” recalls the writer Luis Yslas about their name. “I thought that could be the name, understanding it as a space for gathering in a common space, of similar interests... playing with the double meaning of the phrase.”

In 2013, Yslas and Blanco, along with other associates, opened the Lugar Común Bookstore in the east side of Caracas. The establishment very soon became a stage for musical groups, a classroom for literary workshops and a space for presenting new books. This is how the “Lugarcomunistas” made a name for themselves in Caracas.

However, “now the publishing house and bookstore proceed independently,” clarifies Rodrigo Blanco, the author of three collections of short stories and an unpublished novel.

Since its foundation until today, Libros Lugar Común has been a witness to the passing of time and the changes being generated in Venezuela. In their own words, they have passed through the contraction of the editorial market in 2012, the paper shortage crisis of 2013-2014, and the devaluations of the bolivar that now affect the price of books. What follows is the rest of the story as told to Contrapunto by the founders of the publishing house.

How did you both meet and how did you decide to start the project ReLectura in 2007?

LY: We coincided one afternoon at Pancho Massiani’s house. From then on, we shared conversations, affinities as readers, beers at the local Chinese restaurants (our first and improvised operation headquarters). Two years later, the novelist Federico Vegas invited us to participate in a project he had in mind. He wanted to promote encounters between readers and writers, by means of gatherings, readings, book exchanges, and also through a webpage that ended up becoming a type of literary magazine. That’s how ReLectura emerged.

Is ReLectura —the webpage, the radio program and the book exchange— the embryo for Lugar Común?

LY: Let’s say it was like a training camp and an apprenticeship, since thanks to the work of literary promotion and the editing of digital content, we established a cordial relationship with a group of fiction writers, poets, essayists, critics, journalists, designers, editors and photographers, all of them from the world of reading and writing. Without realizing it, we were preparing ourselves for the editorial work of Lugar Común, since those years also gave us the chance to measure the pulse of what was being written and read in Venezuela.

In what year did the publishing house begin?

LY: Editorial Lugar Común (which changed its name in the middle of 2014 to Libros Lugar Común), is born in 2011, with the publication of the novel El libro de Esther, by Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez.

Who works for the publishing house?

LY: At the moment, those of us who make up the direction and operation of Libros Lugar Común are Rodrigo Blanco and myself, along with a team of people who participate as collaborators, among them Patricia Heredia, who has been with us at the publishing house for more than two years.

From your beginnings to last year, are there significant changes in Venezuela’s publishing field? What might those changes be?

RB: We think many things have changed. In the last three years we’ve seen how, on the one hand, the contraction of the Venezuelan publishing market has increased. Transnational companies like Random House and Alfaguara have left Venezuela. The already existing publishing houses began to suffer the blows of the paper shortage that considerably diminished production in 2013 and part of 2014.

On the other hand, during this same period of crisis we’ve witnessed the emergence of small, independent publishing houses who have come to do the work that was left behind by the transnational companies. And that’s a positive response to the crisis. Towards the second semester of 2014, the rhythm of publications seemed to recuperate, but not without an enormous cost: we’re referring, literally, to the increase in the price of books due to high production costs.

You mention the Venezuelan publishing houses that have emerged in recent years, such as Ígneo, Alhilo Editorial, Utopía Editorial and Negro Sobre Blanco, among others. With the absence of the transnationals and the increased price of books, did Venezuelan literature become a good business? Or, did it become the only means of doing business?

LY: At Libros Lugar Común we don’t think of literature exclusively as a business. It’s true that we believe in the profitability of books and authors, but above all we trust the quality of the product. And if the product is good, there are reasons for trusting that sales will go well. But very few editors dedicate themselves to this work with the idea of becoming millionaires. Making books isn’t a buoyant business, much less at this time, in this country. It’s a bold business that’s worth the risks.

At the moment, the impulse to write seems to be very high in Venezuela. There’s a growing desire to express ideas, emotions, experiences, and to materialize that desire in books. The complex reality we live stimulates writing and reading (although not at the level that certain enthusiasts would have us believe). In that sense, the publishing houses have a very demanding task of selection, investment and production, in order to guarantee the balance between the value and the price of a book, notions that are often confused in the publishing market.

If making books isn’t a “buoyant business,” why keep printing them? For the love of art?

RB: I do think there are actual possibilities for the book business to become a sustainable endeavor and at the same time that it might contribute to the cultural heritage of a country. Why keep doing it? For the love of art and because we still believe in that possibility.

For an independent publishing house in the current context, how many copies should be printed for each edition of your titles? And, of that number, how many copies do you need to sell in order to maintain a minimum margin of recovery and profit?

LY: We live subordinated to an economy that makes any budget volatile. Each week the costs of production and distribution rise. It’s nearly impossible to maintain a business plan that doesn’t feel threatened by a gelatinous and restrictive economy. Which means that internal administration plays a fundamental role.

The number of each of our titles tends to be 1,000 copies, except for the poetry collection which is 500 copies. In order to cover the production costs, we have to sell from 40% to 50% of the copies of each book.

What are the three books you’ve published that have been reprinted the most?

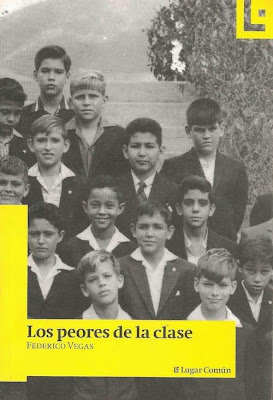

RB: The children’s book Ratón y vampiro, written by Yolanda Pantin and illustrated by Jefferson Quintana; El libro de Esther by Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez; and Los peores de la clase by Federico Vegas.

In regards to distribution, what do you think of applications like Kindle in the U.S. or Librero ETC in Venezuela? Do you distribute your titles through these platforms? Why or why not?

LY: Any project that contributes to disseminating the titles from our catalog is of course welcome, as long as the distribution agreements benefit both parties. We’re not against digital platforms. On the contrary, the more platforms we have for reading, the more visibility the publishing house, its books and its authors gain. Several books by Lugar Común are already available at the platform Librero ETC.

What books will you publish in 2015? Can you give us a preview of the project El bravo tuki by Jesús Torrivilla and Juan Pedro Cámara?

RB: Because of Venezuela’s situation, it’s difficult for us to anticipate the titles for this year. So we’d rather only mention the ones that are definite for this current four-month period. Those are Ogros ejemplares, by Daniel Centeno, and El bravo tuky, by Torrivilla y Cámara.

Centeno’s book is a compilation coordinated by the journalist Oscar Medina of the artist profiles that Daniel Centeno has been publishing periodically in the magazine Sala de Espera. It’s a compendium of exotic lives, narrated with the rigorousness of good journalism and the plastic expressiveness of a writer like Daniel Centeno, who will surprise readers with this book.

El bravo tuky is, simply, one of the books we’ve most enjoyed reading at the publishing house. It’s the first and up until this point the only serious study (without being boring) of the tuky phenomenon. The work of Jesús Torrivilla and Juan Pedro Cámara combines an academic register of the origins of industrial music, along with journalistic and testimonial work on the protagonists of the tuky musical movement. It’s a book that could have an important impact on the circle of publications about music, postmodernism and cultural studies.

The publishing house is part of Lugar Común Bookstore, located in Caracas. Besides selling books, you also facilitate literary workshops, along with conferences and the presentation of musical groups. Have you considered taking this extra-literary experience of Lugar Común to another city?

RB: Actually, it’s the other way around: at the beginning, the bookstore formed part of the publishing house. At least, that’s how it was first conceived. The publishing house was created in 2011 and the bookstore was inaugurated and joined the Lugar Común project in December of 2013. Now the publishing house and bookstore proceed independently.

{ Hensli Rahn Solórzano, Contrapunto, 7 February 2015 }

No comments:

Post a Comment